Investment Banking Fees: The Complete Guide to Fees in Mergers & Acquisitions

Table of Contents

+ Introduction

+ Types of Investment Banking Fees

+ Retainer/Engagement Fees

+ Why Investment Banks Charge Up-Front Fees

+ How Much Should I Pay in Retainer Fees?

+ Success/Back-End Fees

+ Minimum Fees & Break-Up Fees

+ Other Ancillary Fees & Non-Cash Fees

+ Conclusion

Introduction

Fees are an unavoidable aspect of doing a deal. It is also unfortunate that many a deal-maker is very often cagey about the rate they may charge, why they charge a particular fee and how they relate with one another. Fees vary depending on whether you have engaged a full-service investment bank, a business broker or a mid-market M&A intermediary.

They will also differ greatly, depending on your deal type (i.e. sell-side M&A, buy-side M&A or capital raise). However, the general spirit of investment banking fees remain the same, but the overall costs and justifications for them can vary greatly. In this article, we will discuss some of the more common fees inherent in a transaction, the reason for them and how they may differ depending on the type/size of business, the type of transaction, and the intermediary with whom you would engage.

Keep in mind, such fees may also differ over time as well. As I like to keep all articles “evergreen” time may vary or change the numbers discussed herein so there are no guarantees that things will be maintained at their current status quo.

Investment Banking Fee Types

Fees in investment banking can vary greatly from firm to firm and from deal to deal. In general, deals requiring greater input of time and resources–especially in the <$20 million range–will cost more on a dollar-for-dollar percentage basis. Fees can vary greatly from deal-to-deal and firm-to-firm. In general, the smaller the deal, the greater % you will be asked to surrender. Sell-side deals are often more expensive than buy-side deals and capital raises can be the most expensive to the issuer.

Retainer Fees

A retainer fee is a fixed amount that is paid to the investment banker whether the deal is successfully completed or not. In general, successful investment bankers will require a monthly retainer for each deal on which they represent. A retainer does two things. First, it commits the banker by giving him/her proper incentive to work on the account and prepare the business for its eventual sale. In other words, “you get what you pay for.” Second, a proper retainer also helps to commit the seller to a particular course of action—in this case to either raise money or sell a company.

Depending on the complexity and expected length of the deal, the retainer can vary greatly. For instance, for more complex deals the retainer will be more “front-loaded” thus equalizing the greater risk involved in prepping and selling.

Upfront Fees

Upfront fees are often charged at the time of engagement. In many cases, this is a form of retainer and can often include an upfront retainer fee to ensure the seller is committed. In the event that the work is expected to go quickly an upfront fee could include most or all of the retainer.

Expense Reimbursement

No true engagement would be complete without the need for the consultant to avoid out-of-pocket expenses for things like travel, meals, paperwork and entertainment. Typically all such fees associated with a deal are billed directly to the client.

Success Fees

Each deal can generally stand alone, but many are based on the Lehman Formulas shown above. One thing similar with almost every deal is the fact that most success fees are offset by the amount already spent on company retainer costs. That is, retainer fees are generally subtracted from any final success fee.

Minimum Fees

Depending on the size of the bank you’re dealing with, each ibank will require a minimum close amount for any deal. This amount could range from $100,000 to $1 million and is often dependent on the experience and size of the firm or the size of the deal itself.

Retainer/Engagement Fees

Often, and sometimes surprisingly, one of the most hotly debated fees in at least the lower mid-market is the client engagement and retainer fee. This fee can either be charged up front as a standard flat fee or is often drawn-out and invoiced on a monthly basis, with at least some larger portion of the fee due upfront. Depending on the depth of experience within the firm, the size of the transaction and thus the amount of up-front work required to take the opportunity to market, retainer fees may range anywhere from $30,000 to over $100,000. Sometimes such fees may be exacted up-front, while other firms may allow for monthly invoicing of say $5,000 to $15,000 per month. Some firms may provide a refund of at least part or all of the retainer fee upon successful deal closure, but not all.

We will typically never go below $5,000 dollars for a monthly retainer, regardless of the size of the particular deal in question. Those on the lower end of the size spectrum, typically have more of an issue in taking a retainer fee when doing the deal. This is true for a number of reasons. First, they do not like paying out a decent amount month-over-month with no guarantees of eventual deal closure. In addition, some owners are wary of the finance-types coming in and slapping them with large fees. Finally, some owners do not like the idea of feeling overly committed to a deal. In other words, nothing lost, nothing gained gives issuers a greater reason to back out if something goes awry. The following key points outline some of my most compelling reasons for not balking too hard at paying a retainer fee:

- It commits the seller to the course of action. Like earnest money when buying a house any deal-maker wants to know the seller has some skin in the game. It’s a way of committing to the particular course of action. In this way, the retainer fee should not be too small to make it easy to walk away. That is why some larger banks will charge larger fees for larger clients. Charging a larger fee is done not because it requires that much more marginal work than a similar, smaller client, but the larger fee is often used as a psychological tool. The logic there is: the more it stings, the more committed the seller is to sell. If the seller has no skin in the game, s/he can back out at any moment and ultimately the advisor and his firm is left holding the proverbial bag.

- It helps to cover the intermediary’s fixed costs. Despite what the seller may think, the intermediary typically has his own high fixed costs inherent in prepping and working each deal. Most retainers are not usurious by any means. They are simply a way of helping to assuage the total costs of running a business that’s highly human-capital-intensive, not to mention the cost of compliance. Most advisors and bankers do not make their money by charging retainers, it just helps them not to lose it.

- It incentivizes the intermediary. If an intermediary and his/her team were working several deals at the same time, with some paying retainers and others not, then those clients not paying the fee will typically become the “if I have time after I serve my paying clients, then I’ll move over to this charity case…” That’s not a good situation to be in if you’re a motivated seller looking for a reputable firm to do your deal, as reputable firms will always have other clients with whom they’re working and they don’t have time to work for free.

Other upfront and ancillary expenses may be charged with the retainer fee. In addition, expenses inherent to travel, etc. will typically be invoiced separate from the retainer fees, but everything–of course–is subject to negotiation. We have discussed engagement and retainer fees previously here.

Why Investment Banks Charge Upfront Fees

Nothing is free. Capital is certainly no exception. TANSTAAFL (there’s ain’t no such thing as a free lunch) applies. In that light, here’s a conversation I play on repeat on a weekly basis.

Potential client: “Do you work to raise capital?”

Me: “Yes, but whether or not we work with a client is dependent on many factors.”

Client: “What are the factors?”

Me: “The team, growth stage, traction, intellectual property, existing cap table AND whether or not they can afford the most minimal of engagements. We also do not typically work with startups, especially those with little to no revenue. Create a solid business and a reason for investors to risk capital first.”

Client: “What?! You charge an upfront fee for raising capital? Why can’t your fees be based solely on the successful requisition of capital?”

The prospective client will then proceed to dive deeper into his/her sales pitch. What should be at most a five minute elevator pitch will almost invariably extend into an hour. I assume they’re under the impression that if they can sell the banker on the viability of their plan/team/idea, that banker will cave to a structure devoid of an engagement fee with something larger on the backend. Truth be told, for every ten pre-revenue firms completely unwilling to pay upfront for capital, there are a small handful of already successful companies with proven revenues and a track-record who are ready to pay for the service of raising capital through an investment bank.

While the aforementioned scenario paints the picture from the capital raise side, balking at deal fees can also occur on the buyer and seller side. However, the most promising and highest quality deals will never balk at deal fees. They “get it” and recognize they’re paying for a needed service. It’s a cost of doing business. My intent is not to overly beleaguer the point, especially for those that understand the need for upfront fees, but to provide clarity for those who cry foul at them–startup or not–and to help such understand why they exist.

Commit the Client

Nothing speaks commitment like a little skin. It’s the pre-deal equivalent of a break-up fee. This is even more glaringly true for buy-side engagements where–without the “skin” of a engagement–the acquirer could walk away at any time without it ever costing them a dime. If for nothing more, an up-front fee provides at least some confidence for the banker that the client is committed to a full process.

While break-up fees are often a sticky negotiation point in the Investment Banking Agreement, engagement fees often represent a much smaller bite and help to alleviate the ongoing costs of the investment bank.

Cover Expenses

Investment banking is a risky business, particularly for smaller boutique, private investment banks. The ongoing compliance and regulatory costs are completely non-existent in other industries. And, unlike recurring revenue companies like those we’ve worked with in software-as-a-service businesses, rarely do we receive repeat business from the same customer. It’s “wham bam thank you ma’am.” Bankers often live and die by the deal. Said a third way, if you want to eat it, you have to kill it. Up-front fees ensures the wolf stays away from the door until the deal is in the can.

Filter the Riff Raff

The reason Berkshire Hathaway has never split Class A shares of its common stock is (in Warren’s own words) to “keep the riff raff out.” The most legitimate entrepreneurs, if they truly believe in the viability of their product, service or team should be able to cobble the friends/family cash together to raise capital the right way. Often the right way includes raising the friends/family round to pay for the engagement fee to hire a bank to raise debt and equity through a full outbound marketing process from individual and institutional investors. Investment bankers–with an understanding of how deals are done in today’s market–will always be better at putting a deal away than internal management. Let the bankers focus on what they do best.

The clients we prefer to work with have revenues of $50 million+ (preferably +) with hefty balance sheets. Such companies have a much easier time attracting capital from institutional players. Investment bankers are also more comfortable working with an existing, established business. Bankers also have a moral obligation to be sure they can put a deal away. I hate to over-promise and under-deliver. That’s bad business.

Truly, “money talks” and “cash is king.” I know what it means to be a startup using bubblegum and duct tape to get by, but understanding that capital has a cost is often extremely difficult, even for those who may call themselves seasoned businesspeople.

How Much Should I Pay in Engagement/Retainer Fees?

In any business consulting arrangement, the consultant is going to require the consultee for some type of upfront money for performance. How much is paid is typically arbitrary and almost always negotiable. The question is, how much should you pay as a retainer for services rendered? As always, it depends. First , let’s ask a few non-rhetorical questions.

- What type of experience are we talking about? How long has the company been in business?

- What does the firm’s professional network look like? Do the founders have what might be termed a Rolex Rolodex?

- What specific skill-sets are you looking for? Will the consultant have the ability to fulfill the requirements of the particular project?

- What type of references can the firm provide? (this is paramount)

What is paid out in a retainer fee is co-dependent on the level of service your firm feels is requisite with the project at hand. It should also be commensurate with the sheer human capital required to complete the project as well as the overall resources required to complete the service needed.

The Three Dials

Fees charged by investment banks include both cash and non-cash compensation. Cash compensation is typically charged in both an upfront engagement fee and a success or back-end fee, typically as a percentage of the overall deal. Non-cash compensation can include warrants or options. As a sweetener, warrants require those holding them to put up money in, typically at a discount to market. These three dials can be turned up and down as needed. Rarely are any of them eliminated.

Shared Sacrifice

We’re consistently asked whether or not we can be paid on strictly a commission basis with no retainer. In most cases, unless the work is pro-bono, we absolutely refuse for a number of reasons. First, in the case of retainers paid for merger and acquisition services, there is typically an out clause in an engagement contract that gives the selling party the ability to walk away from an engagement. A retainer typically helps to seal the commitment of the selling party to the course of action in a transaction. It’s a “put your money where your mouth is” pledge. We don’t work without a retainer for this reason alone. Period.

Second, retainers are fees provided for services paid. In the unfortunate case that a consultant is unable to raise money or complete a deal, they’re not going to be out hundreds of hours of work and effort for naught. It’s not good business to work for free. That’s called charity. In some cases, retainers can be refunded out of any deal success fee, but they’re ultimately just enough to help the surviving entity eek by a living.

Third, retainers provide the seller with capital to take care of expenses they’ll need to work on the project or deal. Advertising and expenses related to pitching the project or opportunity are frequently included in the retainer. Travel expenses are generally not included and billed separately.

Don’t think giving equity or a larger commission portion to your contractor or contracted company will incentivize them. Retainers work best. You ask your salespeople to share in the gains, but most of them should still be paid a base salary. I always have found it interesting that the best salesmen are almost always the ones who demand the larger base. You get what you pay for in just about anything. That same type of scenario holds true with retainer fees as well.

We go back to our original question, “How much should you pay in retainer fees?”

The retainer should typically be enough to feel it, but not enough to hamper cash flows and break the bank.

To answer the question, retainers can range anywhere from $5,000 to $15,000 a month, depending on the need and the services rendered. Some require more. Some require the engagement upfront. I would question the ability and skill of those requiring less. Some also may require a larger portion of the retainer paid up front. If the firm is reputable enough, it may be worth it.

Paying for services can be a difficult pill to swallow. But, unlike products, there’s rarely a P.O.-style format where you rack up a bunch of fees over a period of time, unless of course you’re working with attorneys. In any event, the retainer fee is an often-disputed and more frequently misunderstood aspect of performing projects and doing deals with contractors. When you’re ready to grow your business then sell your business, you typically have to spend money to make money. Just make sure the firm you’re working with can deliver and you’ll find yourself measuring a cash positive ROI.

Success/Back-End Fees

The amount you pay in a success fee, ranges and typically is most dependent on the valuation and/or size of your company. It’s great news for larger businesses, as larger companies tend to pay much less per marginal dollar in deal size than the smaller businesses. This is true for a number of reasons. First, smaller businesses are typically just as much or more work than the larger clients (thanks to both shareholder’s and general deal risks). Second, larger, more established firms with consistent cash flows are frequently much easier to sell. If a business is successfully performing, it is generally much easier to find a buyer.

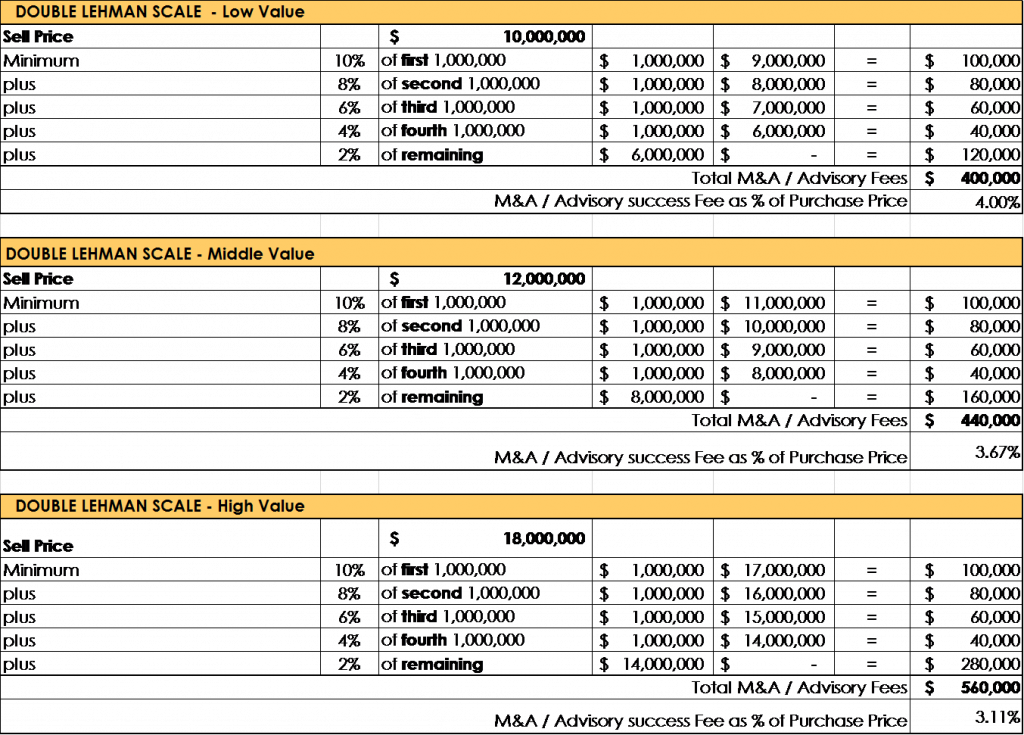

For lower mid-market M&A transactions, expect to pay a standard Lehman formula and, if you’re smaller, a double Lehman–to help cover the excess cost of being small and requiring more human and capital input to get the deal done. Below I have outlined what typical fees might look like in a lower mid-market deal on a double-Lehman sliding scale.

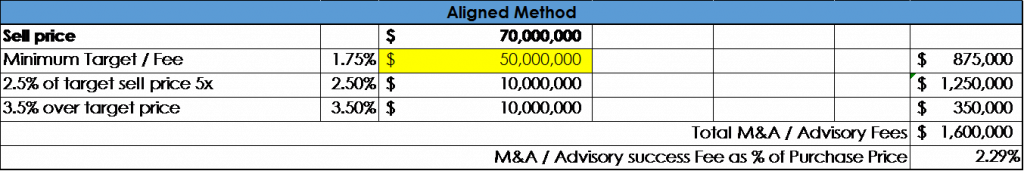

Unfortunately the Lehman and double-Lehman methods leave some holes in the incentive structure for investment bankers. For instance, the Lehman formula does not provide ample incentives for an M&A intermediary to sell the business at the highest possible price. In fact, the reverse is true in the aforementioned formula: for every incremental increase in value, the intermediary or M&A advisor actually makes less money. As a result, today’s thoughtful investment bankers are adopting a strategy often referred to as the “aligned” method for investment banking fees.

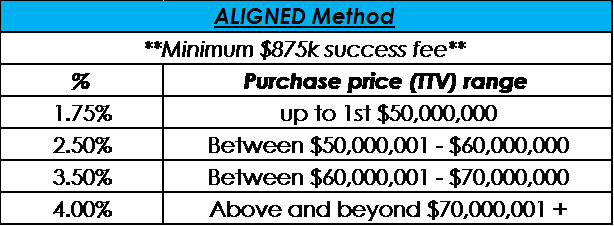

The aforementioned scale–as always– includes the assumption that the investment banker will charge minimum fees. More importantly, sellers should note the overall percentage paid for services rendered remains unchanged and that the incentives to the investment banker for getting the best deal possible for the client are greatly enhanced. In the “aligned” method an investment banker actually makes less than in the double Lehman method if s/he fails to obtain the best possible price outcome from a competitive bidding process. Below you will find a simplified version of the above.

Note that the percentage increase is marginally incremental on the dollars within the purchase price range based on Total Transaction Value (TTV), not back to dollar one. Hence the banker has an aligned incentive with the seller or issuer. It is also helpful to note that in this scenario we are talking about a deal in the $50,000,000 to $70,000,000 price range. Smaller deals that often require more work will demand a higher fee than those mentioned in this example (think double or even triple depending on the size, industry and complexity).

Like I mentioned before, some firms will actually deduct any previous retainers (or a portion of previous retainers) from the final success fee from the business, but this is extremely rare. Some, but not all so it should certainly not be expected. There are a number of other forms of a modified Lehman which are used, some of which are negotiable, but it mostly depends on the firm with whom you have engaged. If your business is a smaller firm and is still in need of good representation, the total fees you pay will likely be on par with the fees paid to larger companies. Typically smaller companies are more difficult, need seller preparation and require more hand-holding throughout the process. These features are a contributing factor to the premium paid by smaller firms. This is at least one of the reasons smaller, boutique middle market M&A shops beat comparable bulge-bracket investment banks in revenues and profitability.

Minimum Fees & Break-Up Fees

When times are good and work is plentiful, minimum fees upon deal closure are charged much less frequently. Minimum fees are often more par for the course in smaller deals, but if your business boasts a much larger EBITDA, has great, solid and diversified revenues, a minimum fee is typically not necessary. In addition, if the advisor/client relationship is worked-out correctly and the seller has an appropriate expectation on value, then the business should sell for at least an expected threshold amount and no minimum fee will need to be paid. Minimum fees also exact more from buyers who’ve built a nice business and should reap more of the compensation at the time of deal closure.

While break-up fees are more rare in middle market deals, they can occur. A break-up fee includes an incentive for the seller wherein the seller is required to pay a fee in the unlikely event s/he backs out of a closely negotiated deal with a quality buyer. A full treatise on investment banking breakup fees is likely worth its own reference.

Other Non-Cash Compensation

In addition to engagement and success fees, many investment bankers will request non-cash compensation in the form of options or warrants. As deal “sweeteners,” non-cash compensation can be a win-win and typically are not exercised until some future date. When they are exercised, warrants can provide a cash infusion (albeit with some dilution) to the issuer and an immediate gain to the investment bank. Non-cash compensation is more typical in capital formation projects than in sell-side M&A transactions.

Conclusion

Very few business brokers, M&A advisors or sell-side investment bankers post their “fees” online. We certainly do not. The reason: no two deal is the same and depending on the size of the deal the amount charge in engagement and back-end fees could vary widely. What is included here is meant to paint the picture as a simple “example” for what one might expect when it comes time to pay and investment banker to manage a sell-side process for mergers and acquisitions. Being too transparent on fees does not benefit the investment bank much. It also leaves less room on the table for negotiating better terms with a potential client. In all, everything is negotiable and if you have built a good enough business that can sell itself, then the chips usually fall in your favor naturally.

- Covid-19 Impact on US Private Capital Raising Activity in 2020 - May 27, 2021

- Healthcare 2021: Trends, M&A & Valuations - May 19, 2021

- 2021 Outlook on Media & Telecom M&A Transactions - May 12, 2021