Mezzanine financing has created opportunities for investors to secure cheaper alternatives to fund companies. The purpose of the article is to present an overview of mezzanine financing and discuss the various features of the debt. Included in the article is a discussion of the benefits and drawbacks associated with mezzanine financing as well as the risk and implications of incorporating mezzanine financing in a company�s capital structure.

Characteristics

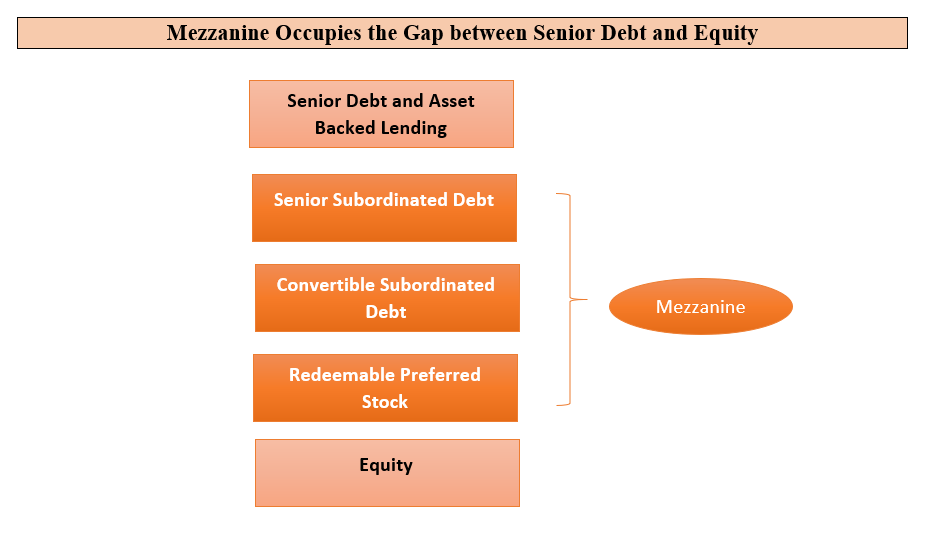

Mezzanine financing, also referred to as quasi-equity, comprises of both unsecured debt or second lien debt and has debt and equity characteristics.[1] Mezzanine financing is a type of loan that is subordinated to the senior debt in a firm�s capital structure but is above the common stock or preferred equity. This form of debt can take the form of senior subordinated debt, convertible preferred debentures or as preferred equity. Such loans are frequently used for financing acquisitions or fueling the fire with needed non-dilutive growth capital. Within a capital structure, it is junior to all debt. Mezzanine debt has a higher interest rate since the risk exposure is more than that of senior debt.[2]

The yields of mezzanine financing are the highest in the bond market and are riskier compared to senior debt. Mezzanine debt financing is usually based on covenant packages such as bank facility covenants or high-yield style covenants. The bank facility covenant often has maintenance covenants and is mostly based on the credit facility�s covenants. High yield covenants on the other hand, can shield a bondholder from unfavorable actions by equity owners and safeguard a bond�s priority of claims.Mezzanine debt that is similar to high yield debt has components such as optional redemption and call protection provisions that are comparable to high-yield notes. Similarly, mezzanine debt that includes some components of senior debt has mandatory prepayments secured to debt and optional prepayments at par, at low or decreasing premiums. For example, some mezzanine notes can be redeemed at 105% of their principal amount in the first year following the note issuance, 104% in the second year, 103% in the third year and 102% in the fourth year.[3]

Benefits and Disadvantages

Mezzanine financing is valuable in the capital structure of a company. For example, the equity capital of a company is strengthened with mezzanine financing since equity holdings are not diluted. Mezzanine financing also enhances the structure and creditworthiness of a company and has a positive impact on a company�s rating.[4] Like equity financing, mezzanine financing does not need collateral, thereby, companies have the flexibility to use capital to expand and to manage the operations of the company. The use of mezzanine debt reduces the amount of equity invested in a company and lowers the after-tax cost of capital. [5] Additionally, the value of stocks held by current shareholders increases when mezzanine financing is integrated in the company�s capital structure.In general, companies that use mezzanine financing have the flexibility to structure covenants, amortization and coupons to adjust and cover exclusive cash flow requirements.[6] Mezzanine investors benefit from mezzanine financing as it generates higher rates of return. Investors also obtain steady returns from mezzanine funding due to contractual agreements to make interest payments.7Conversely, mezzanine debt is high risk and an expensive form of funding as it is the second to last to be paid during a liquidation or bankruptcy of the company. If the company is not successful, mezzanine investors have little recourse. Another disadvantage associated with mezzanine financing is that companies must meet certain financial ratios, must abide by restrictive covenants and may have specific agreements with mezzanine lenders to avoid refinancing senior debt, borrowing more money or creating additional security interests in the company�s assets.8

Risks and Implications

Although, mezzanine financing has high returns, it is the highest-risk form of debt. During a financial crisis, the company may be less likely to pay mezzanine lenders since the senior debt must be paid off first. Due to the high financing risk, mezzanine debt is usually structured during the advanced and matured phase of a company.[7] Although, mezzanine financing can be used to minimize the senior lender�s exposure, it can create complicated inter-creditor issues between the mezzanine investors and senior lenders. For example, mezzanine financing can increase the level of senior liability to a project and senior lending can also block payments for mezzanine investors.[8]One of the implications of incorporating mezzanine financing for young companies is that the anticipated risk and return profile and the default risk of the company must be considered.8 In general, a valuable investment from mezzanine financing will require that investors choose high-performing companies that have a minimal possibility of experiencing financial problems. So long as the company remains solvent, lenders are usually restricted by covenants to engage in operational activities. However, companies can seek lender approval to make significant changes. Due to the nature of mezzanine lending, companies must ensure that mezzanine lenders are valuation experts and have proficient underwriting skills.[9]

Conclusion

Mezzanine financing is gaining interest among both private investors and institutional investors. As a subordinated debt to senior debt and with less risk profile compared to senior debt, mezzanine debt is becoming more common among dealmakers. Companies benefit from mezzanine financing since it enhances the structure of the company, reduces the amount of equity investment and prevents equity dilution. Nonetheless, in the event of bankruptcy or liquidation, mezzanine investors may be at risk for non-payment of returns. Consideration must be made when incorporating mezzanine financing in the debt structure of companies to avoid financial losses.Sources[1]RAJAY BAGARIA, HIGH YIELD DEBT: AN INSIDER'S GUIDE TO THE MARKETPLACE, (2016)[2] Corry Silbernagel & Davis Vaitkunas, Mezzanine Finance, http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~igiddy/articles/Mezzanine_Finance_Explained.pdf[3] Arthur D. Robinson, Igor Fert and Mark A. Brod, Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP, Mezzanine Finance: Overview, (2011), www.stblaw.com/docs/default-source/cold-fusion-existing-content/publications/pub1004.pdf?sfvrsn=2[4] LUC NIJS, PDI EUROPE REPORT, (2017).[5] Axial, Using Mezzanine Debt for Growth, (July 21, 2015), https://www.axial.net/forum/mezzanine-debt-growth/[6] Sheila a. Enriquez, A Higher Yield, STREET BUSINESS HOUSTON, 20, (2009), http://www.bvccpa.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Mezzanine_Financing.pdf[7] CHRISTINE K. VOLKMANN, KIM OLIVER TOKARSKI & MARC GR�NHAGEN, ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE: CONCEPTS FOR THE CREATION AND GROWTH OF NEW VENTURES, (2010). [8] ESTEBAN C. BULJEVICH &YOON S. PARK, PROJECT FINANCING AND THE INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MARKETS, (2007).[9] KIRBY ROSPLOCK, THE COMPLETE DIRECT INVESTING HANDBOOK: A GUIDE FOR FAMILY OFFICES, QUALIFIED PURCHASERS, AND ACCREDITED INVESTORS, (2017).

.png)

.png.png)