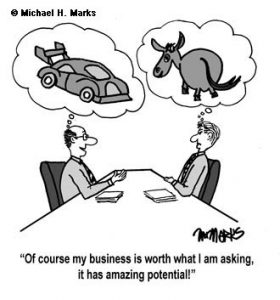

Your business isn’t worth what you think

There are virtually limitless methods for valuing a company. When performed in tandem, multiple valuations methodologies can provide a fair range, helping to set expectations and providing a good barometer for both buyers and sellers. Such differences in value can be dependent on where the business is in its lifecycle. Startups, for instance, often move on a number that stems from capital infusions, often using pre and post money as the gauge. A valuation for 409a for stock options will be different than a valuation performed by an M&A advisor seeking to win over a business owner looking to sell. Each methodology may be correct within the context of their various uses.

Unless the valuation is meant to be held-up in a court of law, there is almost always some degree of subjectivity. With the subjective nature, especially in offering of a company for sale, the seller will nearly always side with the top of the range, expecting and hoping for more than fair market value for his/her shares. What follows is a discussion that helps to clarify why most companies are worth far less than most owners think or wish and why owners often need a reset on their business valuation expectations.

Bloviated Expectations

Today’s Cinderella stories in M&A news have created a very twisted sense of reality for business sellers. There’s a hope that every startup (and even profitable companies) will eventually become a strategic target in acquisition by some large, Fortune 500 firm.

In most cases, company buyers aren’t strategic, they’re financial. The money buyers (private equity groups or family offices) make up the majority of company acquirers. They’re looking for above-market returns. That means their money is made on the buy. Financial buyers rarely overpay and they have very tight valuation based on some cash flow multiple they’ve already set for similar companies within a particular sector.

Today’s financial buyers are regular buyers. In short, they’re in the business of putting capital to work by buying companies. As such, they’re not only familiar with value, they also see a great number of opportunities, many of which are more compelling than your deal. Never use Whatsapp or [insert similar ridiculously valued company here] as an example of what could happen to you.

Public Company Multiples

Private stock can have tremendous value, but its locked-up and illiquid. By nature, it also carries with it its own degree of risk. The private company discount is one of the reasons some folks come to us through ReverseMergers.com, hoping to cash in on a higher market cap by taking their company public. Personally, I not would recommend going public if the only reason is to bolster an arbitrary market cap number.

Being an insider to a public company doesn’t necessarily mean your stock is completely liquid either. Most public company owners must “dribble” their shares into the public market slowly, ensuring the market doesn’t panic, sending the existing shares into a tailspin. The “dribble” must also be done according to rules set forth by SEC/FINRA. Obtaining liquidity through a public offering, especially for companies with less than $100M in sales, is no where close to the liquidity of a full-blown private acquisition. Selling all the stock in one liquid acquisition event, even if the total value is much lower, is most often the preferred method for unlocking liquidity.

Your company will likely maintain a higher valuation if it is fully trading and reporting, but boosting your company valuation by becoming a public company should not be the only motivation for becoming public. The costs and potential liabilities are much too high.

Strategic Acquirer Value

The risk of illiquid stock is further expanded by customer concentration, non-recurring revenue sources, lack of long term contracts and no formidable barriers to entry. These and other factors may scare away even the most interested buyer. As I just discussed, some buyers may have a strategic reason or willingness to pay more for a particular company. While most often not expressed at the outset, this value premium is not easily extracted. Such a buyer will often see such value as their own and will be unwilling to show all the cards.

The best way to extract said value is to have multiple strategic buyers desiring the acquisition of the company at the same time. The strategic buyers with a overinflated willingness to pay are certainly out there, but the rare circumstances that such a buyer would overpay, particularly for a pre-revenue company, is fool’s wish. The proper course of action requires a very custom-structured “corralling” of the right parties to the transaction and the expertise to properly “heard the cats.”

Size Thresholds

The size threshold is most impactful on both business buyers and business sellers in several ways. First, business sellers that run companies with EBITDA in excess of $1M to $2M are typically a bit more sophisticated and have a much more realistic value on what their business is typically worth. This may be true not just because they’re more sophisticated, but also because they’ve been able to save more over their years of profitability, decreasing their need to use the business divestment as their source for retirement. “We’ll be fine whether we sell or not,” is a common statement. That fact alone often creates less stress in maximizing seller value with a strategic M&A auction.

Second, business buyers bring their own dynamic to deals over the minimal size threshold. Rarely do idiots create large and notable enterprises. Consequently, business buyers are much more attracted to companies with higher cash flows. The companies typically have more customer dispersion, less market risk and are often more turn-key as an investment option. In addition, because of the excess capital supply held in many an acquiring business these days, business buyers are more reticent to take on greater risk with companies whose values dip below the $20M mark. Buying a $4M business takes as much time and effort from a buyer’s perspective as a $20M business with less capital deployed and less total return realized.

In general, most small, private companies are worth less than real estate if based directly on cash flow. They’re also more difficult to sell and harder to operate than real estate. As such, company owners and founders often require an “expectation reset” when it comes to true business value. Your business is not worth what you think, so rethink it.

- Covid-19 Impact on US Private Capital Raising Activity in 2020 - May 27, 2021

- Healthcare 2021: Trends, M&A & Valuations - May 19, 2021

- 2021 Outlook on Media & Telecom M&A Transactions - May 12, 2021