I love the following quote by Warren Buffett as it sums up my feelings on business value in a nutshell:

Price is what you pay, value is what you get.

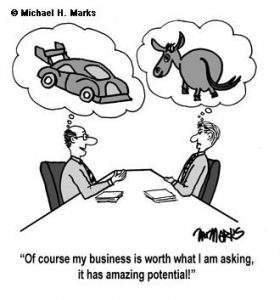

One of the biggest struggles with selling in the middle to lower middle market is business valuation expectations. Sellers almost always feel their business is worth far more than what the market will bear. Here are some reasons why this has been the case:

- The owner is valuing assets and not cash-flows. Investors don't care what you paid for your PP&E even if it has been depreciated in a reasonable matter. In most cases, a buyer is only willing to buy the business based on the cash the company is kicking out month-over-month and quarter-over-quarter. The true value--especially in today's businesses--is not typically in the hard assets, but said assets are able to produce in a cash-on-cash return for investors.

- One of the biggest problems with valuations is what I might call the Instagram, Whatsapp, OculusVR skew. Just because Facebook paid a multiple outside the range of anything reasonable in the real world, doesn't mean your company is also worth 100X Revenues or $40/user. In fact, unless the business has some form of intellectual property combined with the ability to scale in a network-based format, forget about it. You're a traditional business.

- Valuation multiples don't increase if your bottom-line increases. Sure, the business will be worth more if you put more cash flow to the bottom line, it doesn't mean your multiple moves from 4x to 6x.

- The owner/operator is reverse-engineering a valuation based on wants/needs, not on fair market value. As I've advocated before, there are many instances when selling a business is not the right move at all. If you're <50 years old, the business is kicking-off cash and you're looking to retire, but realize you'll need a 7X or more multiple to get there, forget it. Keep operating the company for a few more years.

There could be a host of other reasons, but these are the most common incident to the clients with whom we've recently worked. There are certainly ways to help boost the valuation multiple of the business of up to 40% �above the FMV (that's what our process helps to do), but the exception to the fair value should not be considered the rule. It is tough for sellers and buyers to walk in one another's shoes. Unfortunately for the seller, the buyer is also usually right about what the value of the business truly is. Because buyers typically acquire businesses many times and sellers only sell maybe once or twice, it usually means the buyer is much more sophisticated and knows more about what the market will bear in terms of price. Hence, as an advisor, it's always frustrating when sellers fail to listen to both retained advisory and acquiring firms when they tell them their business isn't worth 12x EBITDA.Invariably, entrepreneurs almost always have a bloated sense of what their companies are worth. This mentality often gets many business owners into trouble, especially those who think they should hold when the time is right to sell. Nowhere was this more prevalent than in 2007 and 2008. With general cash-flows high and multiples flying solidly, many company owners and managers were convinced they could grow their businesses and sell in a couple more years. For those who chose to wait, this proved fool-hearty and in some cases fatal.A Real World Example�In 2007 and 2008 we were working with several different electrical contractors on selling their businesses. Five of eight decided to sell for what at the time were reasonable multiples and great "retirement packages" while the remaining three chose to wait. They did so for several justifications. First, most felt their businesses were worth more than the market would have paid for them, even in the best of circumstances. Believe me, nothing gets better than 2007. The second reason many chose to wait was because they felt they could grow the businesses more and perhaps get more money out of them at some point in the future. Again, not much gets better than 2007, but hindsight is certainly 20/20.With bad timing one of the three owners are now out of business while the remaining have weathered the market trough, but came limping out the other side. Without the market's proverbial crystal ball, it is impossible to know what the market will ultimately do in the next month and especially over the coming years. However, there are a few things we've found helpful in playing the true advisor to clients:

- Help them understand market fundamentals. Some entrepreneurs are more sophisticated than others. Understanding cash flow, industry-specific multiples and general market business valuations on their companies will be helpful in getting some owners to make better�decisions.

- Paint a picture on what the market will bear. With the market fundamentals, we help to paint a picture on what the market will bear in best and worst-case scenarios. This means working to showcase the most recent deals which track in similar size and in the same industry.

- Manage general expectations. Part of our jobs as M&A advisors is to help our clients manage their expectations. Some business owners have visited "sell your business" conferences where a slick presenter has told them their business is worth two to three times what it's actually worth and what the market will fully bear. We work as true advisors. If we think a business is undervalued according to what we've seen in the market, we'll be the first to inform of the good news, but most often we're the bearers of harsh reality and must work to un-train those who were expecting to get more in the sale of their business.

Here we sit, four years after one of the biggest market crashes and bubbles in a generation now with much more street-savvy education behind us thanks to recent experience. Our job as investment banking consultants is to help business-owners manage expectations by understanding and owning the true value of their companies. We always hope for a home-run and strategic buyout where multiples are higher-than-average, but generally the market plays to fundamentals.A Note on EarnoutsSome owners are diabolically opposed to earnouts as part of the deal structure. Earnouts can increase the risk of not getting paid what is expected and can ultimately be a source of frustration, but in some instances they work really well. In the case when an owner has an unrealistic valuation expectation on the business an earnout may be just the thing to keep expectations in check and provide the right incentives to maintain, manage and grow the business post-acquisition. Earnouts of up to 30% of the total deal value are often applied in situations where the seller wants more and is confident the coming 12, 18 to 24 months will see a boost in the bottom-line.When it comes time for owners to prepare to sell, the company will certainly sell much faster if management has keen and realistic expectations on what the company is worth. From our experience, the larger the deal gets, the less this particular problem becomes an issue. That's a topic for another day.We work in Seattle mergers and acquisitions. For more information on selling your business, please contact us.

.png)

.png.png)