Various, alternative business earnings metrics can be used to determine a reliable business valuation. The variance between earnings measurement methods can be wide and the results can be misleading. The worst possible outcome is a scenario in which an inaccurate representation of value is presented. While a good measure of earnings is required to determine value, earnings can be an elusive and ethereal number. EBITDA and cash flow are not the same thing. Consequently, determining the true value of a private company can be a difficult task, particularly if the relied-upon data is less-than-reliable. There are also other knowledge-deficits to consider.Are we talking about a private company or a public company that relies on GAAP? If the company is private, what types of normalization and add-backs have been included in the numbers presented by the company or its investment banker? Before we delve into why these questions are helpful, let�s first discuss the necessary components to performing an effective business valuation and then use those against the very best option available for earnings. Keep in mind, earnings are often in the eye of the beholder. That is, buyer and seller may �thumb wrestle� a bit over which is the most representative of reality. First, you need to nail the other components when it comes to using some �net� number to determine value.

Capitalization Rates & DCF Models

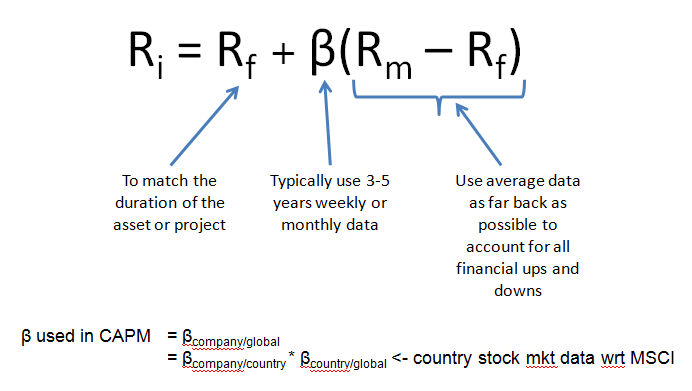

When it comes to valuing a particular business, it is helpful to understand that each business maintains some level of risk. Some of this risk is dependent on the company itself, but included in a company�s risk is its risk relative to other players in that market, modeled against the market as a whole. Risk itself is often best captured using capitalization or discount rates using the most popular build-up or CAPM models.

The discounted cash flow method of determining business value uses forecasted earnings over a future period, discounted against the the chosen discount rate. Determining the proper earnings number--especially when it comes to forecasting future earnings--is often a hotly debated topic among buyers and sellers. This is at least one of the reasons business valuations for M&A purposes often use some earnings multiple of historic data, not some future assumptions based on hearsay forecasting.Larger, publicly-traded companies that have reached scale are often easier to value as you look to predictable future forecasts. Market forecasts for larger firms are often a bit more predictable and future earnings can be based off of recurring revenues streams. In contrast, smaller, middle-market firms not only lack predictability, they also are scant on their relevant industry research. In other words, there are not teams of analysts looking at every aspect of the business to see how it will perform quarter-over-quarter.For middle and lower middle-market companies, determining capitalization rates and future earnings is nigh to impossible, especially if you�re looking to peg numbers on which everyone can agree. There is no exact fit for cap rates and the scant data for forecasted earnings is paltry at best.

Accounting Multiples, Add Backs & Normalizations

When seeking out public company valuation comparables, there are no shortage of relevant earnings metrics. For instance, price to net income, price to EBIT, price to EBITDA, price to gross revenues and price to net sales are readily available from the nearest Bloomberg terminal.Smaller firms on the other hand, do not have analysts or an active market to help determine the real, relative value of the company in question. In other words, there is a knowledge information gap in determining the value of smaller companies. Similar but simpler methods are often used for private business valuations. For instance, Net Cash Flow, abbreviated Net Cash Flow and Seller�s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) are all used in the calculation of that elusive �earnings� number.When certified appraisers gauge the value of a private business, they typically look for normalization or financial statement reconstruction--two more conservative methods at nailing down value. Similarly, investment bankers will look at �add backs.� As a marketing ploy, they will take every possible expense that does not belong and shove it back into the picture like a non-fitting puzzle piece. There is certainly a reasonable expectation that some add-backs will be required, but sophisticated buyers will see through add-backs that venture outside of reason and expenses that will always be included in OPEX.The truth will often come out at QofE time during due diligence--which is a great time to re-negotiate the price because the deal is locked. There are dangers being a public company that is not required to adhere to GAAP or IFRS as earnings measurements are not standardized. There are also advantages. It depends on how things are presented. This is not a wink and a nod for the illegal or immoral, but a hint that �everything is negotiable.� What a buyer is willing to pay is often the result of competition for the deal and not the ultimate earnings multiple.

Public vs. Private Incentives

When it comes to measurement of earnings differences between public and private companies, there are a few basic concepts to keep in mind:

- Public companies are incentivized to maximize their stock price. They do this by looking to boost earnings. At its core, earnings are bolstered by increasing sales revenues or decreasing costs.Private companies are incentivized to minimize taxable income. They do this by including personal expenses (where legal and without piercing the corporate veil) and other creative, but legal, tax avoidance strategies.

- It is also important to note that most private businesses do not pay taxes, the owners do. Unless the business is a true C-corp and taxed as a C-corp, it likely is a pass-through structure such as an S-corp or LLC. In these structures, the profits from the business flow to the owner�s personal K-1 for tax purposes. The benefit: owners can minimize taxes by offsetting additional expenses (some personal, some investment) against the profits of the business that flow to them personally.

Public companies--on the other hand--avoid taxes by moving to new geographies, gaining tax breaks from municipalities or local governments or merging in creative structures like the oft-criticized �tax inversion.� Small businesses unfortunately miss out on many such tax advantages.When investment bankers provide their consulting to middle-market companies, they are often astute enough to extract the so-called �private company earnings discounts� from the business, which have long been the result of tax-incentivized-earnings-minimalization. Doing so can be a time-intensive exercise, but a helpful and necessary one as a business prepares itself for an M&A event.In addition to tax incentive skews, aggressive depreciation--while a boon for saving in taxes--can skew the reinvestment cycle and use timeline of the actual asset in question. Depreciation and Amortization--the �D� and �A� included in EBITDA--are an attempt to solve for this issue by looking at earnings without things like aggressive depreciation, there may still need to be adjustments when real value is sought.Public companies, on the other hand, are typically more true to market as they are under constant surveillance by investors and regulators to not only adhere to standards, but to ensure what sits in the earnings number is a true reflection of the company�s performance.Fortunately, other benefits exist for private businesses that are not available to public companies. For instance, private businesses can take loans from the owners, owners� family members and friends of the company. These back-door deals are not allowed in public companies. These differences too must be accounted for when performing a private company valuation.

Reasonable Valuations & The Valuation Knowledge Gap

Both incentives and lack of sophistication play key roles in how private businesses are valued relative to public companies. In most cases, the numbers quoted from a simple Quickbooks export of a private company�s EBIT or EBITDA do not represent an accurate reflection of the company�s earnings performance. Normalization, adjustments and add-backs may be needed to provide a true market-based assessment of the company�s value. Understanding and accounting for these private-to-public discrepancies is not only important in understanding value, it becomes a key upper-hand through the negotiation process between business buyer and seller. One must assume that the ultimate chosen buyer will understand true value as part of QofE for due diligence and thus render any financial engineering moot. However, reasonable valuation enhancements and adjustments are expected when taking a private company to the market for eventual sale.

.png)

.png.png)